I’ll Jump When I See Them

Written by Ashley Makar | February 2019

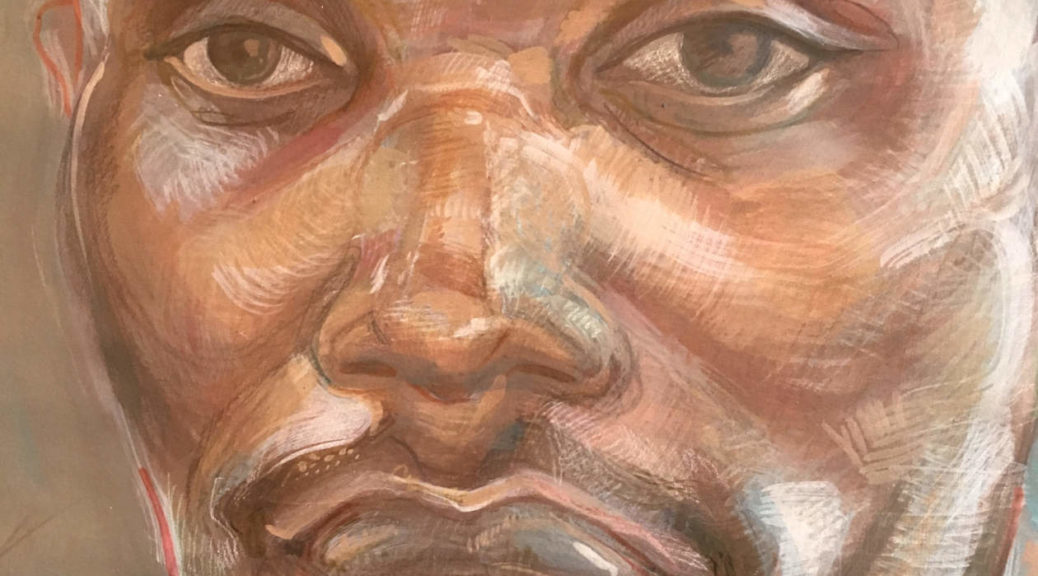

A portrait of Kamal, a refugee from Darfur, painting by Linnéa Spransy

Imagine a Goodwill inside a school, with the vibe of a Cairo airport gate. That’s the scene, on busy days, at IRIS, the refugee resettlement agency where I work in Connecticut. People speaking Arabic, Swahili, Dari, Pashto, and English bustle and wait to see their case managers, with cups of tea and paperwork. Along the walls are world maps and local bus routes, kids’ drawings of planes and stars, flashcards for the US citizenship exam. The donation space overflows with coats; lamps stand over bassinets, pots, and pans.

Reporters used to dash in to do stories on the travel ban. But that was only the beginning of the President’s effort to shut Muslims and refugees out of the country. Through a convoluted series of executive actions, he has decimated the U.S. refugee resettlement program. Millions of displaced people are left in precarious straits.

Working with refugees is unsettling sometimes. Knowing whose brother tried to get to Europe on a raft, who has trouble eating because she thinks about her mom not having food back home, who survived genocide only to get hit by a car. They’ve got so much to grieve while they work long days to make ends meet. It’s not how they envisioned the American dream. But they keep working and waiting for better days, with a resilience I get to witness. They endure in light of the loss that brought them here.

I got to know a young dad named Kamal while he was trying to understand what the travel ban would mean for his family. (Names have been changed, to protect the privacy of the people in this story.) They are refugees from Darfur, a part of Sudan where militias burn villages and massacre civilians. Kamal fled over the border into Chad, where a UN field office determined his eligibility to apply for resettlement to the U.S. in 2013. That was the beginning of an arduous process of interviews and security screenings. Between each step there were months of waiting, with no indication of when or if his application would be approved.

During that time, he worked in the Breidjing camp as a history teacher for other refugee adults, in a makeshift school where he met a young woman named Safa. They got married in 2014. A year later, Kamal finally got the news that he’d been granted resettlement to the U.S. But because Kamal and Safa had started their resettlement applications before their marriage, they were considered separate cases, and Safa was not allowed to join him, even though she was eight weeks pregnant with their first child. They were told he could apply to bring her later, through the “follow-to-join program” that reunites refugees in the U.S with their spouses and children overseas.

Kamal was faced with a difficult choice. If he stayed in the refugee camp, his visa would expire, and he would have to start the process all over again. He and Safa could end up waiting ten years or more, with no guarantee that they would both get resettled in the U.S. If he went, they would be separated, but she might get her visa six in to eight months. Kamal decided to go. He was assigned to IRIS, the resettlement agency in New Haven, Connecticut where there was a growing community of refugees from Darfur.

Soon after arriving, Kamal started his family reunification application. He had to submit photos and other documentation of his wedding in the refugee camp. He and Safa were waiting for the State Department to process her background checks when their daughter Rama was born. They had to complete paternity testing before he could update his follow-to-join application: Now, he was applying to bring his wife and their child to join him in the U.S. After ten more months, they thought they were close. Safa had her last interview with the Department of Homeland Security in January 2017.

Two weeks later, just before Rama’s first birthday, the White House issued its first travel ban. The executive order temporarily banned people from seven Muslim-majority countries and all refugees from entering the U.S.

Before 2017, Kamal and his family had been separated by a bureaucratic machine that moved slowly, but did move. In the wake of the travel ban, they had no idea what was going to happen. Safa called Kamal crying. She and the baby were now in Cameroon—they needed to be close enough to an American embassy for any visa interviews. This was supposed to be the last step in their family reunification process. She told Kamal she wanted to go back to Sudan. She hardly knew anyone in Cameroon, and she didn’t speak the language.

“Please wait,” Kamal told her. “Our country is not safe.”

Before I got to know Kamal’s community, all I knew about Darfur was headlines of genocide. But the Sudanese refugees I know are helping me see the life that doesn’t make the news. Kamal’s friend Ali showed me a home video from Darfur: Ali’s brother is playing a stringed instrument made of tin, sitting next to a man in a suit singing. The people gathered around are standing and clapping along. Someone starts jumping, then another jumps and another, heels to the height of where their knees were. They swing their arms to launch, and up they go, each time like a geyser, and somehow synchronized.

“I love this jump dance!” I said. “What’s it called?”

“Masalit.” It’s the name of their tribe and their native language. “Darfur is the most beautiful part of Sudan,” Ali told me. “On Fridays, you wash all the clothes and hang them outside to dry. You leave the doors open so the angels can come inside.” Ali’s mom is a traditional healer. He remembers her making medicine out of neem trees. She’d started to teach him the healing secrets, he told me. “But then we got war.”

Kamal’s six-year-old nephew Ammar has also resettled in New Haven. Ammar has never been to their homeland, a lake-filled part of Darfur in Western Sudan. Like Rama, he was born on an arid patch of land in Eastern Chad, in a refugee camp where even water is rationed. But he got out in 2015, when talk of a Muslim ban was just the overblown campaign rhetoric of an unlikely candidate.

Ammar came as a toddler, with his parents, siblings, and their dad’s brother, his Uncle Kamal. When I met them at IRIS, he was hiding behind his parents’ legs. Now, he’s a kid who can get up to some mischief on the playground, who climbs jungle gyms and isn’t afraid to go down the slide, who asks you over and over on the swing set to push him high. This is the best medicine I can imagine for what one refugee calls “this disturbing life.”

Kamal’s application to bring his wife and baby to join them in the U.S. was a long haul in the dark, but when I see him with Ammar, I see sparks of light. Ammar is the type of child Emerson must have been writing about in Conduct of Life, the kind whose happiness “makes the heart too big for the body.”

Sometimes Kamal shows Ammar videos of Masalit celebrations on Youtube: People gathered under the trees around a singer or two, and jumping. “Try to do this,” Kamal tells him. “This is your home song.” Sometimes Ammar tries to jump as high as he can to dance along.

About a month before the first travel ban, Sudanese community leaders invited me to what they call a welcome party, a celebration they were throwing for a group of refugees from their home region who arrived to New Haven in 2016.

At the party, I found Ammar sitting next to his Uncle Kamal. Ammar was wearing a button-up shirt with a silver suit vest, looking askance at a platter of watermelon. When I sat down, he asked, “Do you have ice cream?”

“No,” I told him. “I wish I did.”

“Do you have a car?” he asked.

“No, but I have a bicycle.”

“Then can we go get ice cream?”

Kamal showed me a picture of Safa holding baby Rama. At the time, they didn’t know what was delaying their family reunification application. “Since I left,” he said, “my heart has been thinking [of] my wife.” They would talk—across the Atlantic and half of Africa—through a video chat app. That’s how Kamal watched their baby Rama grow—her first tooth, her first word. “Somehow, she knows me,” he told me. “She’s started to say ‘Baba’”—Dad—to his picture on her mom’s phone, to the hand waving at her on the screen. She’d started to wave back.

Meanwhile, the welcome party was turning into a dance-off. “Are you going to do the jump dance?!” I asked.

Kamal shook his head. “I’ll jump when I see them.”

The U.S. used to be a global leader in resettling refugees: people fleeing torture in Eritrea, persecution in Myanmar, insurgency in Somalia, genocide in Sudan, the wars in Syria, Iraq, and Afghanistan. That has changed during Trump’s presidency. With a barrage of executive orders, he has slashed the number of refugees who can come to the U.S. Most recently, he set a record-low cap on refugee admissions—just 30,000 for 2019, less than a third of the annual average since 1980.

Federal courts blocked Trump’s first travel ban. The White House issued another ban two months later, which was again halted by federal judges. Meanwhile, Kamal and his wife were on a roller coaster of U.S. doors slamming shut, then cracking open again, not knowing if Safa and their baby Rama would make it in.

The U.S. Supreme Court ultimately upheld a third version of the travel ban in June, but the resistance in the courts made all the difference for Kamal’s family. It was during that brief legal opening after a federal court suspended the second travel ban that Safa and Rama received their visas. The family would finally reunite in America.