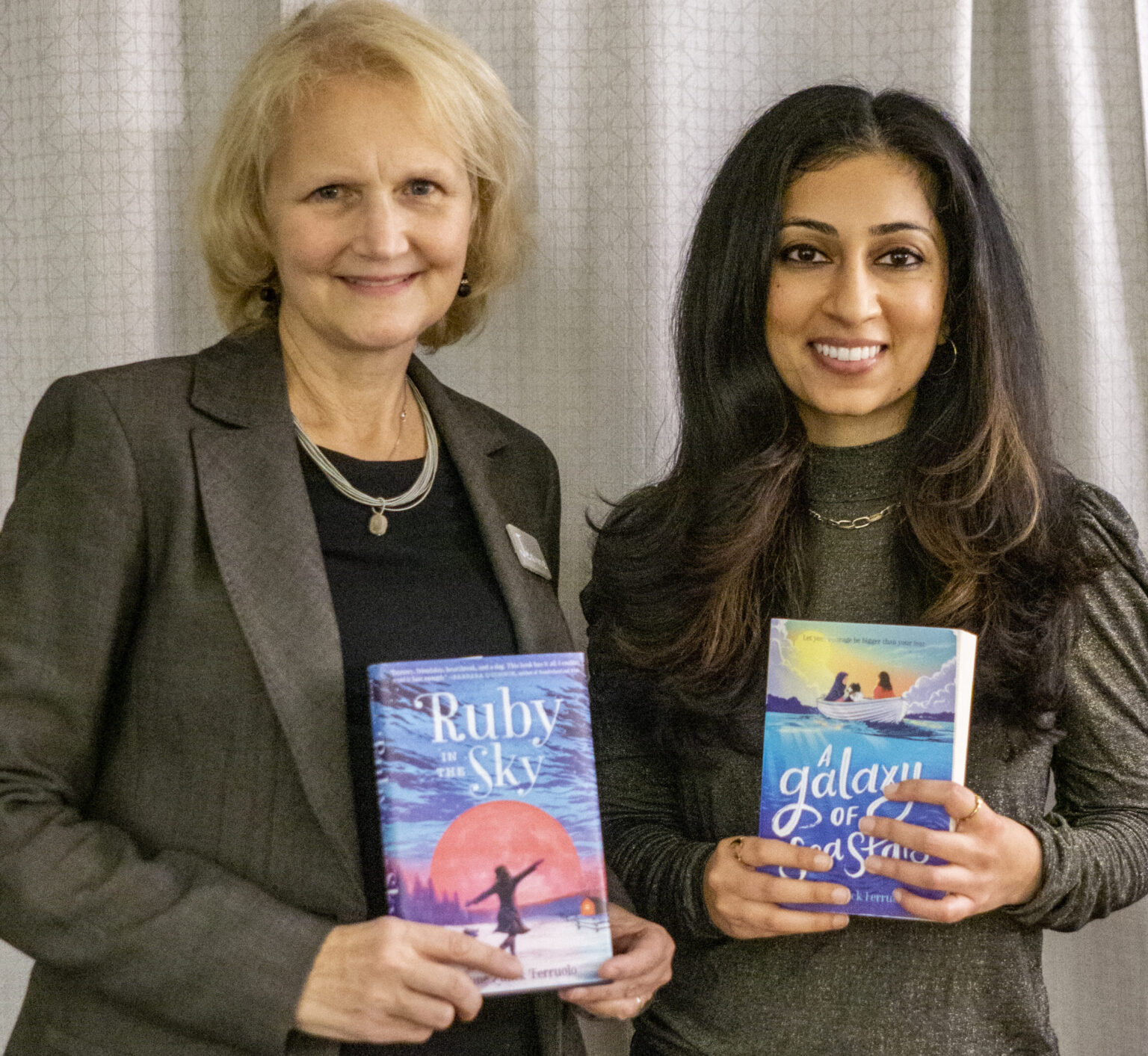

Author works with Refugee Teens to Create Characters in 3 Novels

Written by Grady Trexler

In Ruby and the Sky, Jeanne Zulick Ferruolo’s first novel, Ruby, a twelve-year-old who has just moved to Vermont, learns to be courageous from a new friend, Ahmad, a Syrian refugee. In her second novel, A Galaxy of Sea Stars, when a family of special immigrant visa (SIV) recipients from Afghanistan move into the apartment above eleven-year-old Izzy, Sitara, the family’s daughter, teaches her how to use her voice to speak up for herself and others, even as she faces misunderstanding and teasing–and worse–about her hijab and her halal diet. In her third, and upcoming novel, Each of Us a Universe, Cal meets Rosine Kanambe, a refugee from the Democratic Republic of the Congo, and they attempt to summit a nearby mountain together. Although the characters in Ferruolo’s middle-grade novels are fictional, their lives and experiences are anything but. In fact, Ferruolo worked with IRIS clients — young refugee men and women — to ensure that the events in her stories accurately reflected the true refugee experience, and that her characters were nuanced and faithful representations of the people they claimed to be.

Ahmad, from Ruby in the Sky, was inspired by a friend that Ferruolo’s son brought home from school, a Syrian refugee who shared some of his experiences with her. She knew, however, that she would need help from others who had firsthand experience as refugees in order to finish the novel.

“If you choose to write outside your immediate experience,” says Ferruolo, “it is imperative that you do the hard work required to ensure the story and its characters are portrayed honestly and authentically.” After completing a draft of Ruby, she reached out to several refugee organizations around New England to see if they could help her connect with “sensitivity readers”—editor-readers willing to look over the manuscript in order to comment on its accuracy to their lived experience.

Ferruolo prefers the term “cultural consultants” because of the depth in which these readers enrich the story. “They are truly experts on the culture and experience I’m attempting to write about.” She was hoping to work with careful readers who could help her with everything from the kinds of traditional foods that a Syrian refugee might eat to the way a prayer room could be set up in a middle school.

Ashley Makar, IRIS’s community liaison, says that Ferruolo emailed her asking if it would be possible for her to hire some IRIS clients to read and give feedback on the manuscript.“She wanted to compensate them for their time and also the value of what they’re contributing,” says Makar. She, along with Ann O’Brien, IRIS’s director of community engagement, put together a group of high school-aged refugees that read the manuscript of Ruby and commented on its authenticity. Some of the refugees were Syrian, like Ahmad, and could advise her on specific Syrian cultural values, while others were from places like Burundi, and shared their experiences as refugees more broadly.

“We were so happy because we were kind of writing something to the public,” says Mahmood Alamre, an Iraqi refugee that Jeanne hired to work on Ruby. He says that working as a big group, the refugees were able to comment on what they thought worked, and what they thought didn’t.

For example, in an earlier draft of the story, Ahmad had a different name; the group decided that Ahmad better fit the profile of a young Syrian refugee that Ferruolo had sketched. Mahmood also says that originally, there was a scene in which Ahmad invites Ruby over to his home. He and the others advised Jeanne to change this scene, as it didn’t culturally fit for Ahmad to do so.Alamre says he’s happy that he worked on Ruby because he thinks it will help to expose more people to refugee stories and experiences. He has some experience sharing his story publicly, and says that a lot of folks are surprised at the life of a refugee. “They have no idea what a refugee is and what our life is,” he says.

Consolata Ndayishimye, a refugee from Burundi who lived in a refugee camp in Tanzania before coming to Connecticut, also consulted on Ruby. She says that the editing process with Ferruolo was incremental and organic. The consultants would read the draft, then present some suggestions to Jeanne, who would ask them questions, then write more, then share more writing, then ask more questions.

Makar says that Ferruolo stayed involved with the consultants and IRIS after Ruby was published; at press events, like book readings, Ferruolo invited the refugee youth to speak if they felt comfortable. She also volunteers with IRIS, such as at the annual summer learning program.

Ferruolo began to get an inkling of an idea for a story that included an Afghan SIV recipient–the story that would eventually become Galaxy–and wanted to include refugee youth even more than she already had.“I wanted the voice of Sitara to be their combined, collective voice,” says Ferruolo. For Galaxy, she met with a group of young refugee women even before she had written anything, and developed the story in conjunction with the youth women. Then she wrote the manuscript, and met with them several times over the course of the year, to get their feedback. “It was very illuminating,” says Asma Rahimyar, who consulted on Galaxy after the manuscript was written. Rahimyar, who isn’t a refugee but who was born in Connecticut to Afghan parents, says that it was rewarding to explore the commonalities and differences she had with the other young women.

“I was able to discuss characterization with her, in addition to specifics regarding Afghan culture,” says Rahimyar.

After publishing Galaxy, Ferruolo was struck with an idea for another story, this one centering around two young women–one white, one a refugee from the Democratic Republic of the Congo–and began working with Gladys Mwilelo, who she had befriended some years prior.

Ferruolo says that she consulted much more heavily with Mwilelo than she had with her other two books–so heavily, in fact, that Mwilelo will appear on the cover of the book as a co-author with Ferruolo.

“We discussed the whole story together,” says Mwilelo, who was born in the DRC but lived as a refugee in Burundi for thirteen years before coming to Connecticut as a refugee in 2013. She says that the process began with Ferruolo asking her questions about her life, then writing a bit, then asking her more questions, then writing even more. The character of Rosine in Each of Us is heavily inspired by Mwilelo’s courage and inner strength.

Mwilelo says that she is still surprised and happy about becoming a co-author. “It makes me feel empowered, it makes me want to even do more,” she says. She also says that she is happy to help in a project that will introduce refugee voices into middle grade literature–if refugees are to be accepted into American society, she says, their stories also have to be accepted into American bookstores and libraries. Rahimyar agrees. “I felt lonely for extended periods of time and my solace was always books,” she says, but she never felt certain parts of her identity reflected back at her. She never read about, for example, a protagonist whose name was mispronounced. As an Afghan, she says this was extra hard, given that Afghan culture is so communal and she was in some ways detached from that culture living in the United States.

“Maybe it’s my grandmother’s voice in my head, but I feel compelled to include immigrants in my books,” says Ferruolo, who grew up with stories from her grandparents about their struggles as immigrants to the United States. They came from Austria-Hungary, what is now Slovakia, around 1913, to escape the poverty and direness of the impending war. When they arrived, she says, they faced discrimination; her father, for example, was punished for speaking Slovak in school. At one point, the Ku Klux Klan targeted them–in one version of the story, they burnt a cross in their yard; in another, the cross was in the adjoining graveyard. Either way, the message was clear: the cross was meant for the family. In fact, this story made it into Galaxy, although Ferruolo traded out the cross for the burning of a milk shed.

“Even in her later years, my grandmother was always trying to make sense of this discrimination,” says Ferruolo, which is why she thinks her grandmother was so eager to tell her stories. Ferruolo says that this spurred her own desire to tell other immigrant stories. “Seeing prejudice continue to be waged over and over on each new generation of immigrants has made me feel compelled to share their stories, especially with kids. It is when we learn more about each other that we find commonality. And it is only through education that we make progress.”She thinks a lot about the ethics of representing characters from cultures other than her own; there were some moments, she says, that she wondered if she was doing the right thing after all by writing these characters. For example, one review criticized Galaxy as positing that Sitara’s family only deserved to be in the United States because they assisted the military in the war. It is an interpretation Ferruolo feels is misplaced, since it was several of the cultural consultants who wanted this background to be included.

Nevertheless, Ferruolo maintains the importance of the inclusion of refugee characters via her cultural consultants. “I’ve been given this amazing opportunity to share words and stories with children all over the world. And I’ve been privileged to meet so many phenomenal young men and women through IRIS. It is my hope that my books can provide a platform to amplify their already powerful voices so they can tell their stories the way they want them to be told,” she says. “My place is to serve their voices. That is my number-one objective.” The consultants and Ferruolo have stayed in touch, even as the writing of the books wrapped up. Ndayishimye, who lives in Texas now, says that every time she is in Connecticut, she and Ferruolo get lunch. She also says that Ferruolo encourages her to write her own story, and every now and then, she sends her some paragraphs that she has written for Ferruolo to make notes on.

Mwilelo, too, says that Ferruolo has been a staunch advocate of her own writing. She says that, through Ferruolo, she has learned to not worry so much about grammar or technique and focus on writing down something that is authentic. “The importance of writing is writing your thoughts,” she says.

Mwilelo and some of the other consultants say that they most appreciate the bravery of Ferruolo’s characters, but she, in turn, said that she was inspired by the bravery of the young refugees and immigrants she worked with. While editing Ruby and drafting Galaxy, Ferruolo was undergoing surgeries and treatments for a rare cancer. “Hearing their stories and learning about the obstacles they overcame as they made their way to a new country,” says Ferruolo, “gave me the courage to face what I had to face.”